"Hackers could use a CubeSat to destroy the ISS"

Published on Sat, 29.04.2023 – 12:57 CEST in Politics, covering DLRSatellites in space seem unreachably far away and thus protected from sabotage. But it is precisely this distance that poses a security risk that should not be underestimated. Decreasing costs for the development and launch of small satellites could even exacerbate the problem. The fact that hackers can gain access to satellites was impressively demonstrated at CYSAT in Paris.

The CYSAT in Paris was all about cyber security in space. For a total of three days, experts from all over the world discussed the status quo and future scenarios. And for good reason. In view of the current geopolitical situation, the issue of data security is once again coming into sharper focus. Many of the applications based on satellite technology have become indispensable in our everyday lives. The extent to which we as a society depend on them is demonstrated not least by the fact that satellites are part of the critical infrastructure and are therefore particularly worthy of protection.

Satellite hack possible with hardware worth 1,000 euros

In today's world, a lot of money is invested in protecting the world's information technology (IT). After all, cyber-attacks such as ransomware, brute force or DDoS regularly cripple entire companies and institutions and cause immense damage. But while firewalls and antivirus programs are more or less taken for granted here on Earth, they are not widely used in space. In addition, satellites launched long ago are equipped with hardware and software that is now outdated. This makes them a rewarding and easily accessible target for hackers. This was pointed out at CYSAT by Dr. Sabine Phillip-May of the German Space Agency (DLR). In her session, she explained that hardware worth as little as 1,000 euros would be enough to hack a satellite.

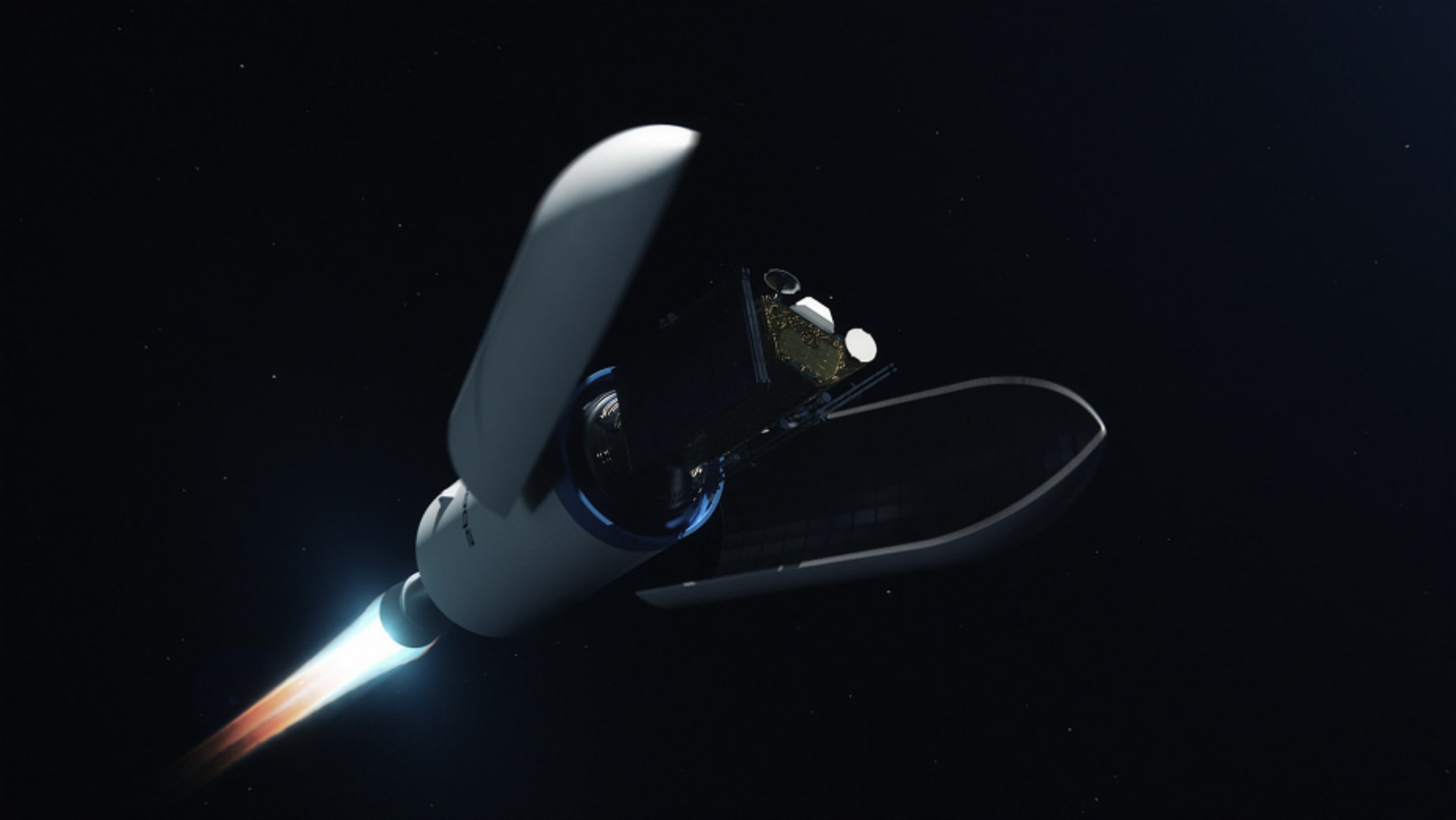

© ESA

Thales hacks ESA's OPS-SAT

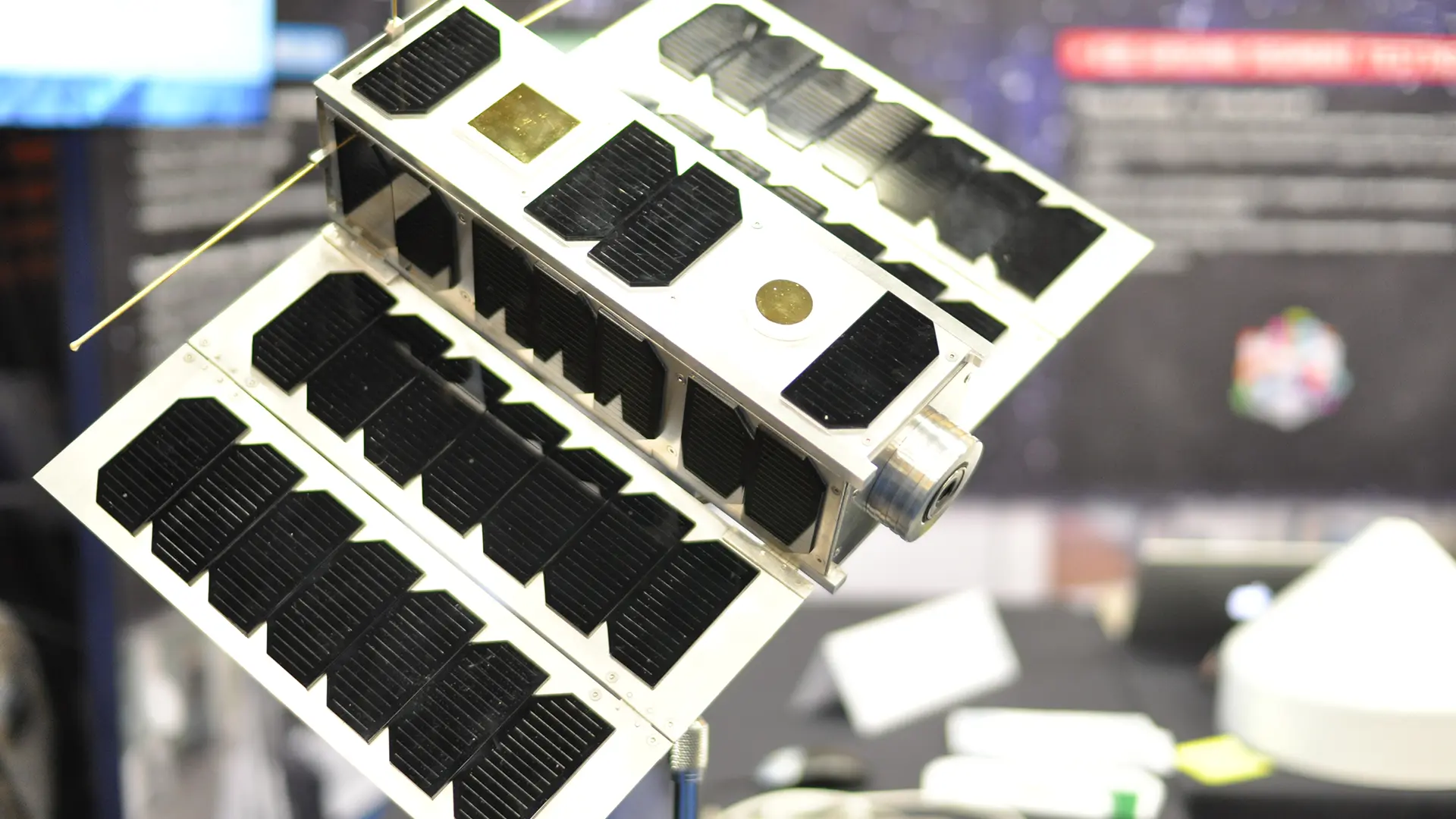

Security experts from the technology company Thales recently proved that this is possible in principle. The target of the "hacker attack" was the 3U CubeSat OPS-SAT of the European Space Agency ESA. It was already launched into space in December 2019 and is considered a flying laboratory. Despite its small size (10 x 10 x 30 cm), it is equipped with a camera for Earth observation, a GPS sensor and a launch tracker for navigation. In addition, a Linux-based computer with 8 GB of RAM is installed next to the main computer, which is available to experts for experiments. So far, more than 130 experiments have been registered on the "sandbox satellite", which is used to test new software directly in space. This is possible, for example, in the area of (optical) communication or flight dynamics, but also in the area of attitude control.

Harnessing more flight computing power than any previous ESA spacecraft, OPS-SAT will be an inflight testbed for all kinds of promising new operational software, tools and techniques.

David Evans, OPS-SAT Mission Manager

Experiments with the camera and automatic image recognition are also possible. This is where the Thales experts came in for the "Hack CYSAT" challenge, which is primarily a training exercise. The aim is to show space engineers how hackers work and what damage they can do to a satellite. Thales' so-called Red Team was asked to propose attack scenarios that could disrupt the actual operation of the satellite. For example, by attacking the on-board computer, the operating system or the various systems available on board, such as cameras or GPS systems.

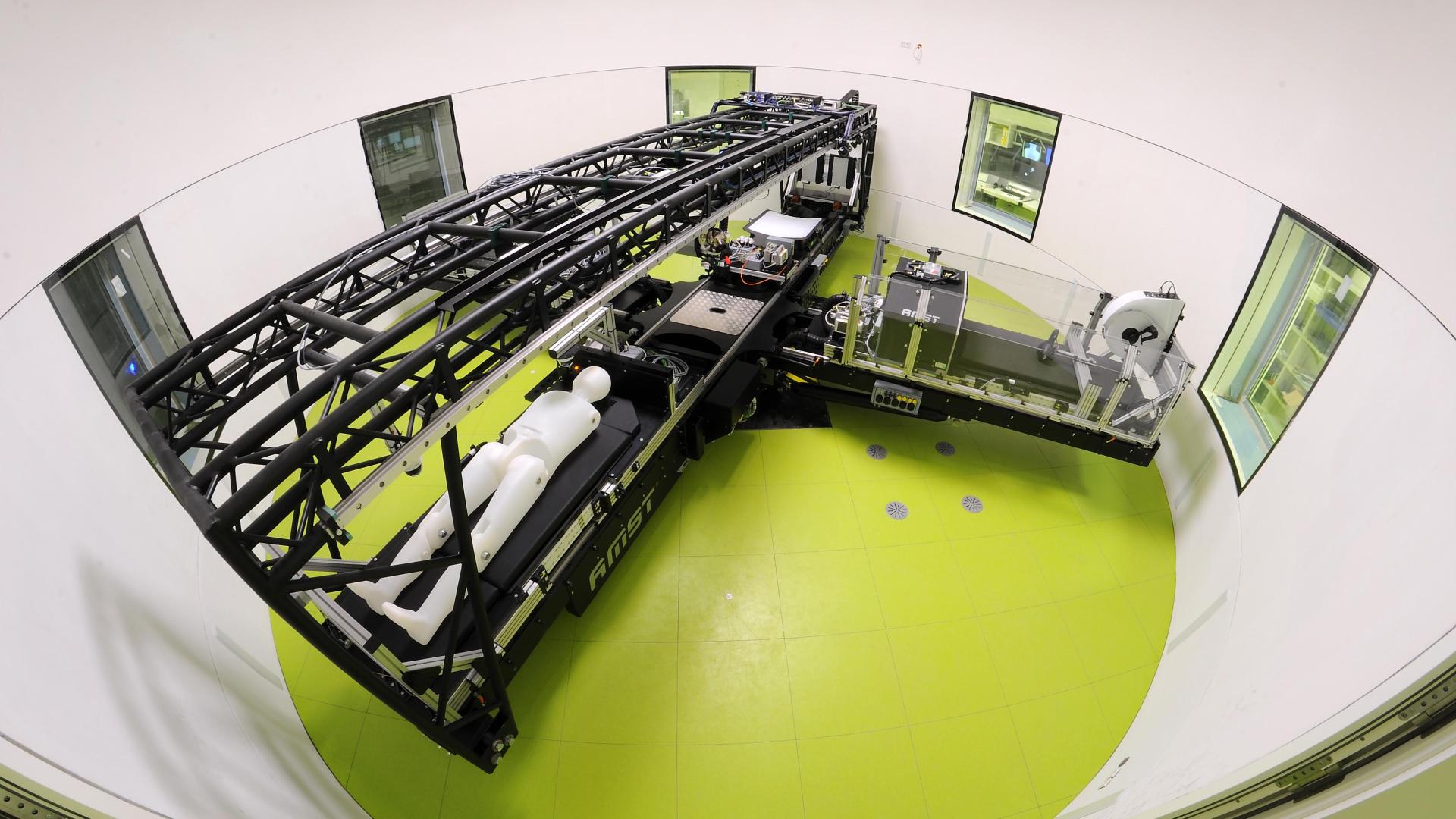

© ESA–Stijn Laagland

At CYSAT in Paris, four cybersecurity experts from the Thales team explained how they managed to gain access to the satellite's control system. Using standard privileges, they gained control of the application layer and then injected malicious code by exploiting several vulnerabilities. This allowed them to manipulate the data being sent back to Earth. Specifically, they altered the images captured by the camera, hiding certain regions of the Earth on the images, and also made changes to prevent the hack from being detected by ESA.

First ethical hack of a satellite

According to Thales, this was the first ethical hack of a satellite. Ethical hackers are experts in computer security and only break into IT systems when specifically asked to do so. Their role is to identify vulnerabilities, assess security risks, and work constructively to fix any security flaws that are discovered. As a result, vulnerabilities were patched after the hacking demonstration, making OPS-SAT more resilient to cyber attacks. As a result, the hackers did not pose a serious threat.

© NASA

But this is by no means a given, as Dr. Sabine Phillip-May pointed out at CYSAT. Particularly problematic are satellites that, unlike OPS-SAT, have their own propulsion. If hackers were to gain control of such a nanosatellite, the consequences could be dramatic. Especially if the trajectory is changed, upsetting the delicate balance of orbits. For example, satellites could be deliberately put on a collision course. A collision would have serious consequences, as demonstrated by the first - unintentional - collision of two satellites (Iridium 33 and Kosmos 2251) on February 10, 2009. This resulted in several thousand pieces of debris at an altitude of nearly 800 km, which are still orbiting the Earth today.

Manipulating satellites poses an enormous potential threat to technology and human life.

In a parallel to the use of ransomware, hackers could extort money in exchange for regaining control of a satellite. Manipulating satellite data, as the Thales team demonstrated, is also problematic. In her session, Philipp-May made it clear that operators of small satellites also have a responsibility to address space-based cybersecurity. She did not fail to mention that she could certainly understand the argument of the associated costs compared to the relevance of the individual satellite. However, when we look at the big picture, this argument falls flat. After all, changing orbits is a massive risk. After all, satellites can become "projectiles" whose sheer speed of about 28,000 km/h can release the energy of about 40 kg of TNT in the event of a collision. It's hard to imagine what would happen if hackers targeted the International Space Station (ISS) in this way.

Awareness of the latent threat situation is expandable

In this respect, it is more than necessary that satellite operators also address the issue of cybersecurity in space. According to Philipp-May, there are many interfaces here, including robotics, cloud applications, Industry 4.0 or the Internet of Things (IoT). On Earth, many security measures have long since become industry standards and have proven their worth. But there are also space-specific requirements. For example, space weather, space situational awareness or anti-satellite weapons, such as those already deployed by Russia, must also be taken into account. The German Space Agency (DLR) therefore wants to create awareness of risks and threats and define responsibilities. The goal is to provide the first approaches for identifying, managing and mitigating risks and threats.

There is no need to re-invent the wheel

In her presentation, Dr. Philipp-May, who is responsible for product assurance and support at DLR's Space Agency, explained that the basic IT protection modules already cover the standard IT aspects of the satellite lifecycle well. A special basic IT protection profile for space infrastructures, developed by BSI in collaboration with two German prime contractors and DLR's Space Agency, was published in June 2022. However, satellite-specific aspects such as on-board software or satellite controls are difficult to map in basic IT protection modules. For these, the DLR Space Agency has therefore developed a risk-oriented approach.

Minimum safety requirements for satellite systems, ground-based operating equipment, as well as facilities for building space assets and their associated supply chains have been developed since 2017. These requirements were established in December 2019 in close coordination and with the acceptance of the German space industry, and were included in a general catalog for product quality assurance. The requirements listed therein are based on established best practices and approaches for identifying vulnerabilities and threats. However, they do not only address the most critical aspects, but also cover risk management as well as security restrictions and controls. The aim is to raise awareness and establish initial meaningful measures.

The "Space Cyber and Data Security" is based on three pillars: "Software Security," "Space Cyber Security," and "Data Security." Software security is complemented by additional topics such as artificial intelligence/machine learning. The ground sector encompasses all three pillars and is supplemented by general IT security and IoT security and therefore treated separately. General emergency and disaster management additionally complements the requirements for all sectors. Many of the principles are by no means new space-related developments. This is also not necessary, as Dr. Sabine Phillip-May emphasized in the concluding Q&A session. She pointed out that the wheel does not need to be reinvented and that one can also learn from others. With regard to the protection of critical infrastructure, this is a valid approach. As Phillip-May stated, "I don't want a million-dollar satellite to have a blue screen!"